Sponsored Article

Sponsored Article

Controlling calf scour in spring-calving dairy herds

Sponsored Article

The approach of spring-calving marks the start of the busiest time of year for Irish dairy herds.

With the aim being to calve the herd within a 12-week window, and the top 5% of herds calving 85% of their herd in the first six weeks of that window, the pressure will be on the whole team to meet the challenges that such a system presents.

With calves arriving thick and fast with the onset of calving, the calf rearing systems of spring-calving herds experience pressure quickly – resources, space and labour can be stretched, as they attempt to meet the demands of calves arriving 24 hours a day.

The value of these calves, many of which represent the future of that herd, is significant, and so these calf-rearing systems need to ensure that despite the challenges, the health and welfare of the calves is maintained.

With a key feature of spring-calving herds being the need for heifers to calve at 24-months-old in order to fit into the system, it is paramount to achieve good growth rates from birth.

Prevention of disease is therefore vital, to ensure optimal growth rates are achieved.

The aim when attempting to prevent neonatal calf scours, and indeed the principle applies to many other disease areas, such as Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD), is to:

- Maximise the calf’s immunity

- Minimise the disease challenge it faces

The challenges of the spring-calving herd in terms of numbers of calves being born in a short space of time, and the pressure that puts on the system in terms of labour, means that these two factors must be considered well ahead of the calving period and thought put into how best to achieve them.

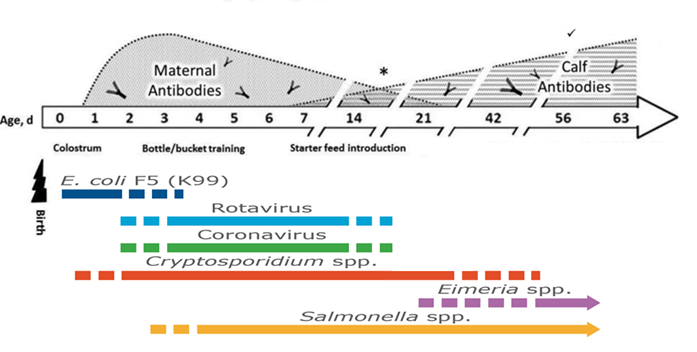

The below diagram shows the most common causes of infectious diarrhoea in young calves, and the age at which they generally cause disease.

Many of these pathogens are ubiquitous on farms and can cause disease alone or in combination. Although we can reduce the infection pressure, we cannot eliminate them from the environment - therefore any control strategy must ensure calves have as much immunity as possible.

There are multiple factors that contribute to maximising an individual calf’s immunity but the contribution of colostrum to this cannot be overstated.

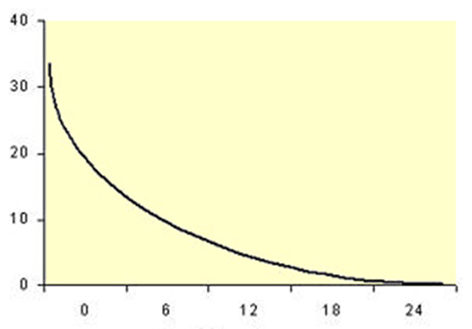

Calves are born with a weak immune system, and therefore depend almost entirely on absorption of immunoglobulins from colostrum after birth for protection - the ‘passive transfer’ of immunity, until their own immune system is effectively functioning.

The ability of the calf to absorb these immunoglobulins decreases quickly after birth, with the gut effectively ‘closed’ to absorption by 20-to-24-hours-old.

Quality

- Each cow’s colostrum should be measured for quality before feeding. Poor quality colostrum should be discarded;

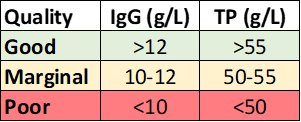

- Good quality colostrum is classified as colostrum containing >50g/L Immunoglobulin (IgG);

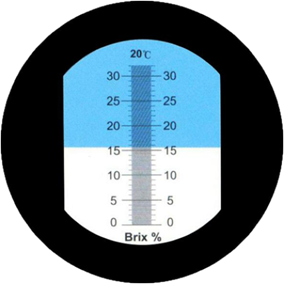

- Quality can be measured with a BRIX refractometer. 22% indicates 50g/L IgG⁸;

- An alternative is using a colostrometer however colostrum should be measured at room temperature (22⁰C) with colostrum measuring in the green zone considered good quality;

- Colostrum quality reduces quickly after calving so cows should be milked as soon as possible.

Quantity & Quickly

- All calves should receive 10% of their bodyweight in good-quality colostrum within the first 6 hours (ideally first 2 hours) after birth, and this should be repeated 12–24 hours after birth;

- Colostrum should be fed at body temperature;

- Ensure there is a store of good quality colostrum from cows of know health status available should additional colostrum be needed.

Colostrum collection & storage

Research finds that bacterial contamination of colostrum is often considerable at the point of feeding, and that this will have a significant impact on uptake of IgG.

Pre-milking teat disinfection, and disinfection of colostrum collection and feeding equipment is paramount.

- Colostrum must be hygienically collected & stored to reduce bacterial contamination;

- Colostrum should be used, pasteurised or stored within an hour of collection;

- Colostrum can be stored in a fridge (4⁰C) for up to 24 hours and in a freezer for up to a year;

- Before use, colostrum should be thawed using warm, not excessively hot, water baths (less than 50 °C) and fed at 38°C.

Rates of successful passive transfer varies across farms but a study of 7 dairy UK dairy farms showed 26% of calves failed to receive adequate immunoglobulin transfer.

Regular testing of blood total protein (TP) or IgG levels of calves < 7 days old allows the approach to colostrum management to be monitored on farms.

This can be done by the farm’s vet on small numbers of calves, with the target being >85% of calves having had successful passive transfer.

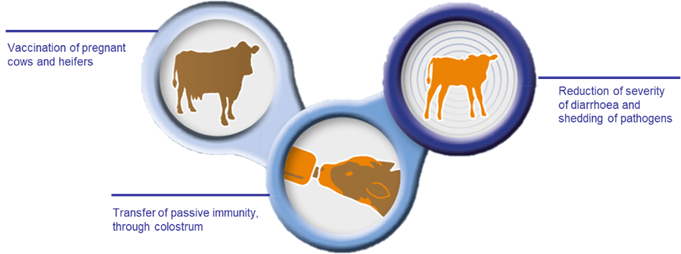

Another means of maximising calf immunity in relation to the prevention of neonatal scour is the use of maternal vaccination.

Vaccinating the cows prior to calving increases the antibody levels of the colostrum to some of the key infectious pathogens that cause scour in the first weeks of life.

Studies have shown that calves fed colostrum from vaccinated dams have less severe diarrhoea and for a shorter duration than calves fed colostrum from unvaccinated dams, they have also been shown to shed the infectious pathogens for a shorter period, which will help reduce the contamination of the environment and the challenge to the group.

Vaccination is another means of maximising a calf’s immunity, however, as it is dependent on good passive transfer, the importance of achieving the 3 Qs remains.

Other factors

- Management & nutrition of the cows pre-calving – whilst beyond the scope of this article, it is important to consider management & nutrition of cows prior to calving to ensure their ability to produce high quality colostrum for their calves;

- Take measures to prevent concurrent neonatal diseases such as BRD, which may compromise the calves’ immune systems;

- Ensure good quality nutrition beyond colostrum feeding to meet calves’ requirements for growth and maintain health;

- Environment – in addition to a focus on hygiene, pay attention to calf comfort (including ambient temperature) to ensure calf’s immunity is not compromised by energy demands to maintain body heat;

- Feeding method; Calves should not be left with their dam and relied upon to suck adequate colostrum. Calves should be fed colostrum by stomach tube or by bottle (and ‘topped up’ by stomach tube if they do not consume the full volume) to be confident the required amount has been ingested.

Although much can be done to maximise a calf’s immunity, in an environment of overwhelming challenge, these animals can still succumb to disease. Therefore, farms must focus on both areas when working to prevent calf scour.

The key to controlling calf scour pathogens is hygiene. The pathogens that most commonly cause infectious calf scour in young calves are rotavirus, coronavirus & cryptosporidia. They are ubiquitous in the environment; and so whilst they cannot be eliminated, they can be controlled.

The aim is to reduce the infection pressure, or the number of these pathogens in the calf’s environment - to a point that they can tolerate without causing disease.

Viral and bacterial pathogens are mainly disseminated from mother-to-calf in the calving pen, or from older calves (particularly those recovering from scours) to younger calves.

Focusing on keeping the cows as clean as possible and minimising the time the calves spend with their dams, will help reduce the exposure of the calves to the pathogens, as will minimising contact with older and / or scouring calves when moved to the calf housing.

- Calve cows in individual calving pens where possible, to reduce exposure of new-born calves to calving yards;

- Minimise time calves spend with the cows to reduce the risk of picking up infection from their dams;

- Clean out & disinfect individual calving pens between calvings – ensure calving pens are made from materials that can be effectively cleaned;

- Don’t forget calf-transport – ensure any trailer/cart used to transport calf is effectively cleaned & disinfected between animals – this too can be a source of infection.

Disinfection & hygiene

- When cleaning calving pens, calf housing, feeding equipment etc., ensure an effective disinfectant is chosen;

- Hydrogen peroxide-based products performed best against cryptosporidia in a recent study comparing commonly used on-farm disinfectants;

- Make sure a new batch of disinfectant is mixed fresh each time;

- Read the instructions – different disinfectants require different mixing rates and contact times;

- Allow time for drying where possible;

- Consider the addition of steam-cleaning into the cleaning protocol – temperature impacts efficacy against some pathogens.

Sick pens

- Consider the use of quarantine or ‘sick pens’ for scouring calves where they can be managed separately from the healthy calves;

- Use separate equipment for the sick calves eg., feed buckets, stomach tubes, protective clothing;

- Remember zoonoses – some pathogens that cause diarrhoea in calves can also affect humans, so ensure staff are aware of the risks.

Managing environmental conditions will also help reduce the build-up of pathogens and disease challenge.

Calves require a clean, dry bed in well ventilated but draught free (<2m/sec) conditions. Moisture and humidity provide conditions favourable to pathogen survival, so ensuring it is controlled where possible will help limit the pathogens.

Farms manage their calf housing in many different ways, but block-calving herds can find space an issue, particularly towards the end of calving.

Hutch/igloo-type housing can provide additional housing, which have the added advantage of being moveable - therefore the ability to re-locate them onto ‘clean’ ground between calves.

The intensity of the calving season makes pre-planning essential for these herds. The creation of protocols and standing operating procedures (SOPs) well ahead of the start of calving, will be invaluable in the midst of those high-pressure weeks of calving.

Sponsored Article