IBR remains a 'significant concern' for Irish beef sector - study

Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR) is still a "significant concern" for the Irish beef sector, despite a drop in prevalence of the disease, according to a new study.

The study of IBR testing results in beef herds, carried out by Dr. Maria Guelbenzu, IBR programme manager with Animal Health Ireland (AHI), is based on data from the National Beef Welfare Scheme (NBWS) 2023.

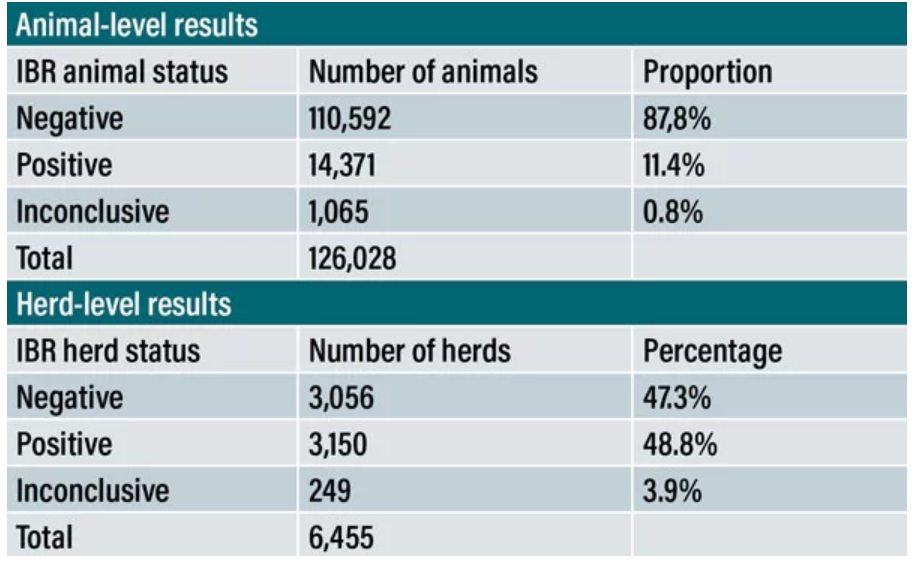

The findings highlight a herd-level prevalence of 48.8% and an animal-level prevalence of 11.4%, "indicating that IBR is endemic in the population".

Although these these prevalence rates reflect a reduction from previous studies, Dr. Guelbenzu said that they "underscore the persistent challenge posed by the disease".

The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) introduced the NBWS last year to enhance animal health and husbandry on Irish suckler farms.

The scheme supported farmers in meal feeding suckler calves in advance of, and after, weaning and in testing for the presence of IBR in their herds.

IBR is a highly infectious respiratory disease caused by the bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1). BoHV-1 is one of eight herpesviruses known to infect cattle.

The disease can manifest in various forms, including respiratory, reproductive, and neurological signs, and can have significant economic implications for cattle farmers.

In total, 10,650 beef breeding herds submitted one or more samples through the NBWS IBR testing programme.

This accounts for approximately 20% of the entire Irish beef herd population.

Among the 126,028 study animals, 14,371 returned a positive result, which meant an animal-level apparent prevalence of 11.4%. At the herd level, the data indicated a herd-level apparent prevalence of 48.8%.

In 51.3% of tested herds no positive animal was detected, while in a further 15% of herds the snapshot of within-herd prevalence was less than 10%.

To determine the herd-level IBR status, a ‘snapshot’ test sampling of 20 randomly-selected animals over nine months old that were used, or intended, for breeding.

The herd-level status for the disease was determined based on the presence of IBR antibodies in the tested animals. Herds were classified as positive if at least one animal within the herd tested positive for antibodies.

The results from the study, published in the Veterinary Ireland Journal, show that, IBR remains "endemic", albeit at a lower prevalence than previously reported.

Dr. Guelbenzu said that this decline may be attributed to various factors such as improved biosecurity measures; vaccination strategies; or changes in farming practices that have contributed to a reduction in transmission within herds.

Around a third of positive herds had a within-herd prevalence below 20% which suggests that targeted interventions in these herds could lead to rapid containment and potentially facilitate the eradication of IBR on a broader scale.

The study also highlights that a higher proportion of herds than previously thought would be in a position to pursue IBR-free status in the context of an IBR programme.